LANGUAGE

ACQUISITION

Jump to videos ︎︎︎

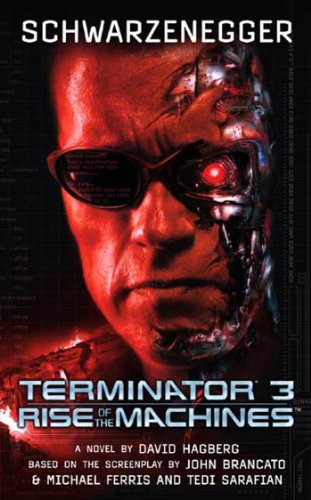

When we think about the singularity, we probably all think about something akin to Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines. ![]() I first watched the film at the same time I was reading essays about nanoparticles, which are these ridiculously tiny particles that go undetected by the human eye. They are measured in nanometers (hence the name) and are only slightly bigger than the size of a single atom. These particles are also special given that their chemical properties vary greatly from their larger counterparts. But why does this matter? Well, in Terminator 3, the malicious computers are the ones controlling these ubiquitous nanoparticles and only casually plotting to use them to wipe out the entire human race. No big deal, right? 🤔

I first watched the film at the same time I was reading essays about nanoparticles, which are these ridiculously tiny particles that go undetected by the human eye. They are measured in nanometers (hence the name) and are only slightly bigger than the size of a single atom. These particles are also special given that their chemical properties vary greatly from their larger counterparts. But why does this matter? Well, in Terminator 3, the malicious computers are the ones controlling these ubiquitous nanoparticles and only casually plotting to use them to wipe out the entire human race. No big deal, right? 🤔

I remember one night when I was visiting my parents in the spring of 2019. When I arrived home, they sat me down to break the news: “we’ve been listening to this podcast that predicts the singularity is going to happen in 2039.” That was only twenty years from then. And then they said: “in the podcast, the host describes the best case scenario is that humans become computers’ pets. But the worst case scenario is that humans become computers’ food.” Shortly after, we left the house to walk the dogs in the dark (which I always thought was a far from optimal time to be discussing things like the meaning of life). My dad decided to ask: “but if that happens, and we become either pets or food, what will be the point of human connection?” ☠️

This project, Language Acquisition, actually takes the opposite position. The narrative asks something different: what might it look like if computers—instead of using our data to take over the world—watched us benevolently to learn as much as they could about human society and language?

Depending on what language theory you subscribe to, you may or may not believe me when I say that there is a lot of hidden language on the internet. By this, I’m referring to code. So if you don’t subscribe to the theory that code is a “natural” language, then maybe you also don’t want to say that there is a lot of hidden “language” on the internet, sure. But, without a doubt, we can look at code and see that code is made up of collections of letters and symbols and those letters and those symbols are on the internet. They’re the foundation of software, they’re on all of our machines, and they make it so we can work from home or video chat with our friends, or shop online. Those symbols and letters might not be a “natural” language, but they do mean something. They do have significance. Computers read those letters and those symbols. They make sense of them and, in doing so, they process information and data for us. They process a certain type of language, though they do not engage in “natural” human language. 🖥

The excellent novella, Fox 8, written by George Saunders, is narrated by a fox who is obsessed with human language. In order to learn this language, Fox 8 peers into the windows of humans each night, listening to their conversations. Of course, he often gets it slightly wrong like in this quote:

“We do not trik Chikens! We are very open and honest

with Chikens! With Chikens, we have a Super Fare Deel,

which is they make the egs, we take the egs, they make

more egs. Not Sly at all. Very strate forward.”

Saunders’ style shines through in this novella; his astute ability to capture tone through form is well suited for a story about a fox learning to speak “Yuman.” Saunders’ fox also enacts linguistic experiments. His understanding relies on phonics. His experiments are of the listening order. At the start of his listening, it would be safe to assume that this little fox did not even know there were corresponding written symbols to supplement his memory and his ears. His misspellings and strange elisions are endearing. They also graphically point to something larger. The fox doesn’t totally get it. And I mean this beyond the formal level: this fox does not bring the same context to the language he learns. He’s not going to be privy to the politics that are embedded within it or of the social implications of that language, because he’s a fox. The content of what the humans are saying means something different to him. 🦊

There’s a brilliant experimental Portuguese poet and author, Salette Tavares, who undertook a similar project years before Saunders. In 1979, pages of Tavares’ text, Irrar (this is a neologism combining “ir” and “error,” which reference both one who walks/wanders and also one who errs), were first exhibited as part of her exhibition Brincar (to play). In the text, Taveres expertly plays with language. Given its made-up form, the word “irrar” ignores orthographic conventions. In this way, Tavares precedes a similar sonic play that Saunders would later employ, in English, in Fox 8.

Without initially knowing it, Language Acquisition has been informed by these two projects. I translated this idea of a “neutral” receiver for language (read: fox) into the contemporary. What if the “neutral” receiver was the computer? What if the computer was just trying to understand? 🧐

In this way, I have attempted to subvert the common narrative of the drastic possibilities of machine learning, to first reflect on humans instead. After all, we use language in devastating ways. We use words to police and exclude, to surveil and track. We use words to hurt each other and we use words to avoid things. Sometimes, we don’t like to call things what they really are. But maybe our computers are on to us? Maybe they’re learning from us so that they can do a better job when we are gone. ☄️

In addition to the work of Salette Tavares and George Saunders, this project is inspired by essays I read while participating in Dr. Manuel Portela’s course, Digital Writing, and conducting research at the University of Coimbra. I am particularly inspired by Johanna Drucker’s text “Writing Like a Machine: Or Becoming An Algorithmic Subject” as well as N. Katherine Hayles’ text on “Virtual Bodies and Flickering Signifiers.” Drucker’s text informs the narrative position of the computer in this piece; however, unlike Drucker’s argument, this position is far from objective. I swing in nearly the opposite direction,

because I do not know if it is possible to truly write like an algorithm, but maybe I can perform being one instead. Hayles’ theory of flickering signifiers comes in at the very end.

This project has been made with support from the Fulbright Foundation and the University of Coimbra. I would like to thank my inspiring classmates, fellow Fulbright grantees, my many watchers and many readers, and the friends I have made during these past 9 months in Portugal. 💖

Jump to videos ︎︎︎